Hip Anatomy

THE HIP

Your hip joint plays a vital role in everyday movement, allowing you to walk, bend, sit, and stay balanced. As the largest weight-bearing joint in your body, it provides strength and mobility while supporting much of your body weight.

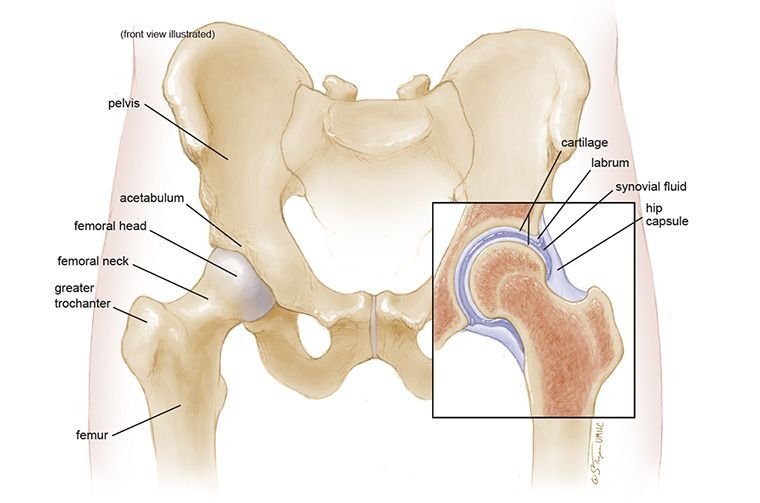

The hip is known as a ball-and-socket joint, where the rounded top of your thigh bone (femur) fits into a curved socket in your pelvis (the acetabulum). Together with surrounding muscles, tendons, ligaments, nerves, and blood vessels, your hip joint allows for smooth, stable movement.

When your hip joint is affected by arthritis, injury, or degeneration, it can cause pain, stiffness, or difficulty moving. Understanding how your hip works is the first step in recognising what might be causing your symptoms, and what can be done to help.

The structure of your hip joint

Your hip joint connects your upper leg to your pelvis and is made up of the following key components:

- Femur – this is the thigh bone, which forms the “ball” part of the joint

- Pelvis – made up of three bones (ilium, ischium, and pubis) which come together to form the socket

The femoral head (ball) fits into the acetabulum (socket), allowing the joint to move freely. A layer of smooth tissue called articular cartilage lines both the femoral head and the socket. This cartilage helps reduce friction and absorb shock during movement.

Key landmarks of the femur include:

- Femoral neck – the narrowed area beneath the head

- Greater and lesser trochanters – bony prominences that serve as attachment points for major hip muscles

Figure showing hip joint anatomy

Ligaments that support your hip

Strong ligaments help hold your hip joint in place and prevent it from moving too far in any direction. These ligaments form a fibrous capsule around the joint to maintain stability.

Key ligaments include:

Iliofemoral ligament

A Y-shaped ligament at the front of your hip that limits overextension.

Pubofemoral ligament

Helps control outward movement of the thigh.

Ischiofemoral ligament

A small ligament inside the joint containing a blood vessel that supplies part of the femoral head

Ligamentum teres

Helps control outward movement of the thigh.

Acetabular labrum

Acetabular labrum – although not a ligament, this cartilage ring plays a major role in keeping the hip joint stable

The Muscles and tendons that support your hip

Muscles around your hip joint allow you to move your leg in different directions and support your body when you stand or walk. These muscles are attached to your bones by tendons.

Important muscles and tendons include:

Gluteal muscles

Including gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus; these control hip extension, rotation, and sideways movement

Iliopsoas

A deep muscle that flexes your hip (important for lifting your leg)

Adductors

Help bring your leg back toward the centre of your body

Rectus femoris

One of the quadriceps, helping with hip flexion.

Hamstrings

Run down the back of your thigh and assist in hip extension.

Iliotibial (IT) band

A thick tendon along the outer thigh that stabilises your hip and knee.

Movements your hip joint allows

Your hip joint is supplied by several major nerves and blood vessels that support movement and keep the tissues healthy.

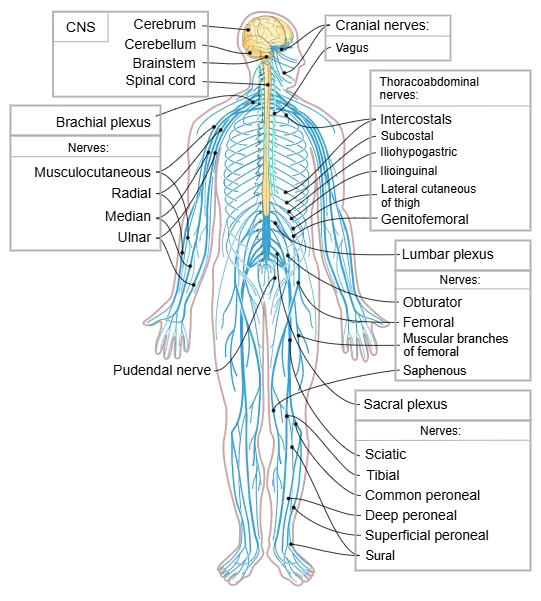

Nerves

- Femoral nerve – controls the muscles at the front of your thigh

- Sciatic nerve – runs down the back of your leg and provides sensation and muscle control

- Obturator nerve – serves the inner thigh area

Blood vessels

- Femoral artery – a large artery that supplies blood to your leg and hip

Smaller arteries within your joint capsule also supply the femoral head and surrounding bone

Movements your hip joint allows

The design of your hip joint allows for a wide range of motion, including:

Flexion

Bending your leg forward (like when sitting)

Extension

Moving your leg behind you

Abduction

Lifting your leg away from your body

Adduction

Bringing your leg back toward your midline

Rotation

Turning your leg inward or outward

Circumduction

Circular movement of your leg

When the joint structure is healthy, these movements are smooth and pain-free. When the joint is damaged or inflamed, these actions may feel stiff, restricted, or painful.

Hip Assessment

During your consultation, Dr Paterson will not only consider your symptoms but will also carefully assess the specific structure of your hip joint using clinical examination and imaging such as X-rays, CT scans, or MRI.

Factors may include:

- Joint alignment and leg length

- Shape and coverage of the socket (acetabulum)

- Shape and rotation of the femoral head and neck

- Signs of arthritis, cartilage wear, or impingement

- Bone density and internal structure (important when planning surgery)

These details help guide treatment – whether that’s non-surgical management, joint-preserving surgery, or total hip replacement.

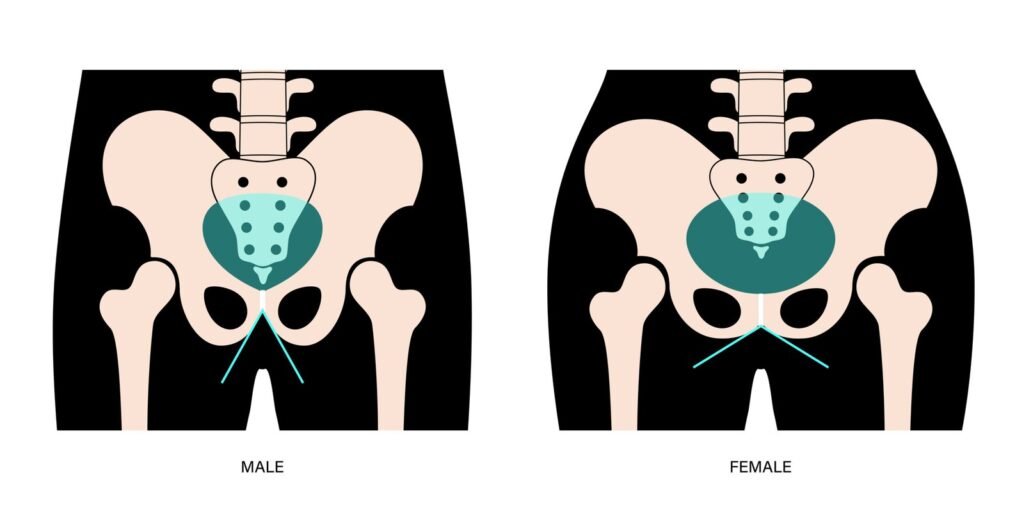

How male and female hip anatomy differs

Your gender can influence how your hip is structured, and this is taken into account when planning surgery or rehabilitation.

Anatomy of a male and female hip

Pelvic differences

- Female pelvis: typically, wider and shallower, with a broader angle at the hips

- Male pelvis: usually narrower and deeper, with a more vertical alignment

These differences can affect how your muscles work and how load is transferred through your hip joint.

Fermoral Differences

- Women often have a smaller femoral canal and a slightly different angle at the femoral neck, which may impact implant sizing

- Men tend to have denser bone and larger femoral components

Dr Paterson uses these anatomical details to guide implant selection, surgical technique, and post-operative rehabilitation, ensuring your treatment is tailored to your body’s needs.

Supporting your recovery and mobility

Understanding your hip joint gives you a clearer picture of what may be causing your symptoms and how treatment can help. Whether you’re managing early signs of arthritis, recovering from injury, or considering surgery, Dr Paterson will work closely with you to create a treatment plan that supports your long-term mobility and quality of life.